This book is often mentioned during online discussions about the history of hygiene, usually by people who haven’t even read it but who blindly believe CheatGPT or Grok because these LLM’s often mention it.

So of course I had to go read it.

Here’s my review, I’ll go through the book and share some of the most interesting bits.

I’ll first share the quote and respond underneath.

I love that the book begins at the very beginning, the history of our hygiene begins even before we were humans:

I’m obsessed with Skara Brae, yes there you will indeed find one of the first known examples of indoor toilets, sewers, etc. on earth.

And they knew how to party!

The hot stone (or clay ball) technique allows you to get cold water to boil in mere seconds and as fires were pretty much burning all day in most houses and you could leave these rocks in the fire for hours, technically you’d be able to get yourself some hot water in no time and with minimum effort 5000 years ago.

Unfortunately the very interesting find of an Bronze age outdoor pool and steam huts in near the Dutch city of Nijmegen didn’t make it into the book, you can read more about that by clicking here.

Sweat baths were everywhere!

When I tried to fact check this, I failed to find the mention of soap, I checked several translations and they all seemed to be talking about an ointment.

600BC!

Stone baths, sitting baths, running water, in Europe, over 2000 years ago.

This is quite impressive, that’s a high number of bathrooms, in much of the world it would take many centuries before so many houses had one, in much of the world this is still not the case today, even among affluent middle class households.

It is fascinating how far back the standard of hygiene was already set, the washing yourself in a metal tub would be how millions of people would do it for 1000s of years, as recent as the 1960s it would be very common for people to bathe or wash themselves in a (often zinc) tub by the fireplace in the kitchen.

This image is not in the book but too good not to share:

And here’s a painting by Edgar Degas from 1886, also not in the book but too good not to add to the article to illustrate the way people have been washing themselves since Ancient times:

The public baths originated with the Ancient Greeks, at least in Europe.

Although the book does mention Mohenjo Daro of the Indus Valley Civilization (modern day Pakistan), it doesn’t mention their (probably public) bathhouse.

It is fascinating to read this as this was exactly how it was done during the middle ages.

We move on to the Roman era;

Although this seems like a lot, the Roman empire was very big and lasted very long and as the book says, the fancy Roman bathhouses were not a common part of life everywhere in the empire.

In many places they would still just be using steam rooms or perhaps tubs heated by the baker’s fire, as people had been doing for 1000s of years.

Important to remember that although we still look at the Roman era as being very clean & hygienic but that appearances aren’t always as they seem.

Medieval London had many more bathhouses than two, just saying.

I sometimes wonder that when people talk about the collapse of the Roman era and the chaos & decline that followed, they may be focusing mostly on England or even just London.

Because things seem to have been a lot more extreme there than they were in many other parts of Europe.

This is something I’ve been saying for a while, always nice to see someone agree.

Yes, the Roman Thermae culture declined, of course, they were too big, too expensive and dependent on slave labour.

You need crowds, traffic and not having to pay your slaves to keep the hypocaust going.

When the Romans withdrew the cities with these huge Thermae often lost many of their customers but also had to start paying their workers.

Europeans had been (steam)bathing before the Romans arrived, during their rule and continued to do so after the Romans went home.

When Thermae closed smaller bathhouses replaced them, often in larger numbers.

Unfortunately this is difficult to prove, most of them were not massive marble, tiled, stone palaces to joy with sophisticated water systems, they were often just regular houses, with at the most a drain in the floor and maybe an oven.

Many of them didn’t even have an oven but shared one with the baker next door.

This leaves little to nothing for archaeologists to discover and of course for a very long time archaeologists also believed Medieval people didn’t bathe very much so when a house with a drain gutter in the floor was discovered and perhaps with an oven, they didn’t think it could have been a bathhouse and wrote it down as a barn or baker.

Interestingly it is possible that these smaller bathhouses were in some ways more hygienic than the Roman Thermae.

Many Thermae had big pools that were used by a lot of people, they were also difficult to clean, replace the water, etc.

Most Medieval bathhouses had a steam room and the option for you go enjoy a bath in a tub, on your own, perhaps with another person, but the big pools were relatively rare.

Hospitals are pretty important, but I can’t find evidence for this claim and there are sources that suggest (not prove) hospitals or similar institutions existing in India, Sri Lanka, Ancient Greece, etc.

Finally, the book has reached the middle ages 🙂

THANK YOU.

I can’t believe we still have to keep reminding people of this today.

Although of course not all lavers were nice fixed stone washbasins, the hanging laver was very common and we see it in art all the time:

Although tubs, basins, bowls, etc. appear in documents, wills & inventories of homes, it’s not always clear what they were used for.

I personally think that tubs big enough to wash & bathe in and used for this purpose (although just a sitting bath) were quite common, but I’m not sure we can state this as a fact.

This is fascinating.

Linen is antibacterial and actively combats dirt, sweat, bad smells.

The text suggests that the Romans may have been influenced by the German tribes to start wearing underwear but that’s not the case.

The Romans did learn about (hard) soap from them though!

Linen, especially when not on display, could easily be washed with rough strong soap, in hot water, without fear of it being damaged and it also didn’t matter much if the stains went out.

This explains how sweat baths were possibly really quite common before, during & after the Roman era.

Many of the bathhouses in Medieval Europe offered their patrons baths, but the steam bath was often even more popular.

Although this is true, there were also quite a few bathhouses were women & men bathed separately and where men spying on the women could get in serious trouble.

So it both happened, Germans still seem to enjoy being naked quite a lot, don’t ask me how I know.

Anyway, I do like the claim of Northern European bathing culture being similar to the one in Japan.

This is also important to note, yes, the church was very powerful and played a huge role in everyday life but we shouldn’t assume that people took everything the church told them seriously.

See, this is what I meant earlier, the post-Roman bathhouses were smaller, simpler but likely much more common.

And they rarely leave any archaeological traces because they were often just rooms in regular houses.

So the weekly visit to the bathhouse was a common European custom but we should also not forget that people washed daily.

Today most people still shower daily but only have a bath once a week or even less often than that.

And although it may seem like the bathhouse culture declined rapidly after the 15th century, it continued on for quite a bit longer in much of Europe.

Here for instance is an 17th century eyewitness account of a Saturday bath in Switzerland;

This sounds like fun, although of course the writer’s idea of being fully naked might not be what we think it is as there’s mention of wearing shirts or bath-coats.

15th century Baden in Switzerland had two public baths and twenty-eight (!) private baths,here’s a description of a visit to one of those in 1416;

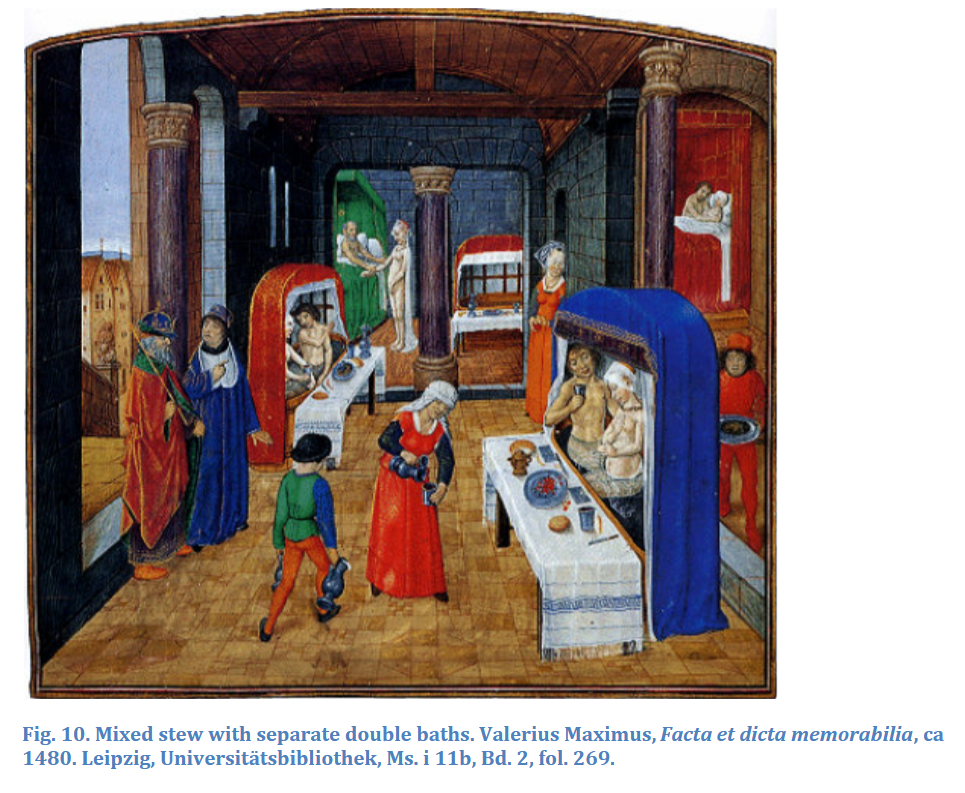

This book was published in 2008, before several groundbreaking books were published on medieval hygiene that dealt with a few myths & misconceptions, the following claims come close to how I thought about bathhouses before those new books came out:

Books like ‘Het middeleeuwse openbare badhuis’ by Fabiola van Dam (2020) and ‘Urban Bodies: Communal Health in Late Medieval English Towns and Cities’ by Carole Rawcliffe (2013) explain convincingly that the idea that most or even many bathhouses were brothels and places of naughty hanky panky is not quite right.

One of the issues is that medieval people used the same term for bathhouses as they did for brothels that also offered bathing services, namely Stews.

But most bathhouses were used by families, as mentioned earlier, you’d go there with your spouse and kids, you’d meet your neighbours, not really a good place to play naughty games.

I think the author of this book didn’t mention that clearly enough and leaves the reader wondering if the bathhouses deserved that bad reputation.

They didn’t.

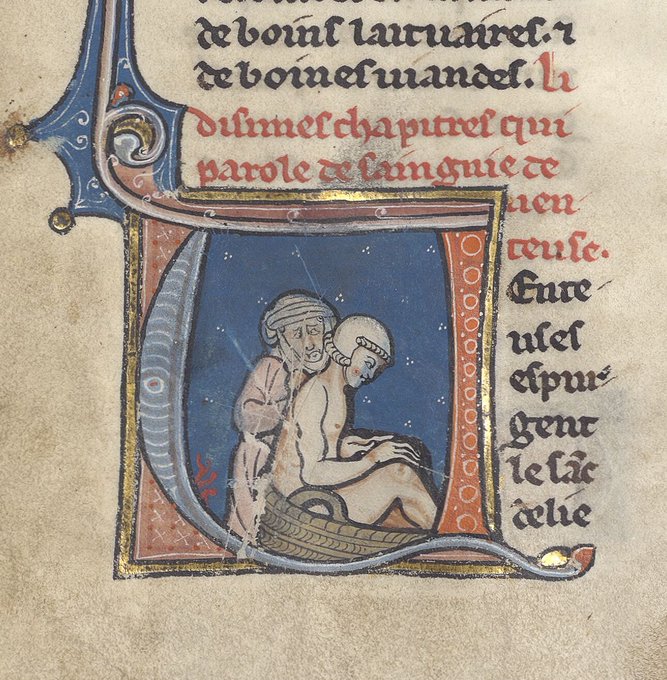

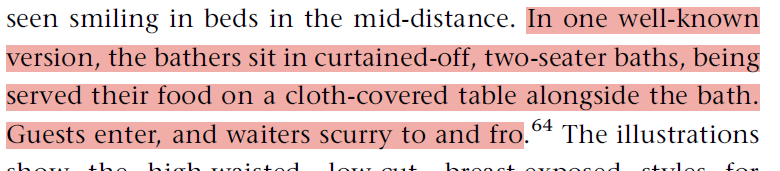

The author means this illustration;

But we have to be careful to accept this as an authentic depiction of a bathhouse because the illustration, although set in the middle ages, is actually part of a Roman story, so the artist is depicting what he thought a Roman bathhouse looked like although he set it in his own time.

So he was likely inspired by Medieval bathhouses but we’re often shown illustrations like these with the claim they show what things were like in those places, but they’re often connected to Roman stories.

Another confusing aspect is that they sometimes show different events happening in the same image, you can see a couple bathing and sharing a bed, but sometimes its the same couple and you’re supposed to know that they first had a bath and then shared a bath, not that one couple was bathing while another one was using a bed for more than just sleeping.

Now we get to the controversial topic of how bathhouse culture declined in Europe:

Although several bathhouses were indeed closed, it was not all of them.

Plenty continued to operate after this period.

And in for instance the Low Countries & Germany bath culture remained popular for much longer, in some places bathhouses were a common and popular part of life into the 1600s, even 1700s.

But yes, bathhouse culture did start to decline after the middle ages, bathing & washing did not though, it just moved away from public bathhouses to more private settings.

There indeed was not a single cause, I agree that it was mostly a combination of fuel costs (deforestation made wood more and more expensive, making it very difficult to keep bathhouses running with a profit) and syphilis that had arrived from the Americas and that seemed to flare up around bathhouses, perhaps because bathhouses were often used for certain medical procedures like blood-letting or because the records confused brothels for bathhouses.

But the idea that it had to do with the plague is one I do not believe, I also wonder which recent historians the author means.

The plague had been repeatedly wiping out millions of people since Roman times, it kept returning, every generation would experience the plague after the Black Death, most more than once or twice.

Yet it never seems to have made people avoid bathhouses for a longer period of time.

Sure, when plague arrived people would stay away from busy popular places (like bathhouses), that’s common sense, as we all learned during Covid.

But once the epidemic had burned out, people would return and life would go back to normal.

I find the idea that even though the plague returned every decade or so people in the 1500s suddenly decided that avoiding bathhouses was the thing to do.

This bit is about post-Medieval Europe, but actually also describes the middle ages in a way, water carrying, public fountains, conduits, public pipes being tapped was all happening long before this point in the book.

More about that in ‘Water technology in the Middle Ages’, by Roberta J. Magnusson (2003) and ‘Community, Urban Health and Environment in the Late Medieval Low Countries’ by Janna Coomans (2021).

Interestingly this too seems to have happened before this time as well.

In Clifford’s Tower in York, an impressive thirteenth-century building, a lavatory was built

for King Henry III, it also had a sort of spout that would flush the toilet with water from

a rainwater-filled cistern on the roof.

Some sort of technology was used to start the flushing, but nobody knows how it worked.

Still, it is (so far) the oldest technical flush toilet known on earth!

It was discovered after this book was written though.

I always enjoy the debunking of that old nonsense about Elizabeth I not or rarely bathing… which is why I was disappointed when I read the next bit;

The author repeats a long debunked myth and fake quote without questioning it.

I myself take care of this story here; The curious claims about Elizabeth I’s bathing habits

Lots of people using soap in the 17th century?

Did they perhaps continue bathing after all? 😉

The story about Louis not liking bathing is a misunderstanding, the quote comes from his physician who was specifically talking about therapeutic/medical baths, not regular baths.

Doctors would now and then prescribe special baths for their patients, these were not fun.

These baths often had extreme temperatures, uncomfortably hot or cold, the water contained strong herbs or even chemicals, the bath could last very long, could involve bloodletting, emetics, purgatives, cupping, or enemas, etc.

It had to do with the humors, part of the miasma theory.

So when in old documents people say they didn’t like baths, you need to figure out if they meant baths the way we have them, or those semi-torturous experiences the physicians prescribed them.

Either way, at least the author mentioned he was cleaned daily.

I’m not sure I believe this, we know they existed in the middle ages, were quite popular in the late middle ages, we know Samuel Pepys & Shakespeare wrote about bathhouses and they remained quite popular, although not at the same scale as during the middle ages.

But maybe I mis understand the context of this part.

I think this text is a little exaggerated, I read the text but didn’t get the idea that public baths were generally widely distrusted, those who had issues with them were part of institutions, medical professionals, not the general public.

The College of Physicians had concerns about regulation and potential abuses, which is not that different from how things had been for centuries.

Bathhouses had bad reputations but the people seemed to have cared a lot less about this than was later assumed.

A step forward or back?

Regular bathing & having furniture to help you wash was a common thing in Medieval Europe, it seems to have returned in the 18th century, but was it ever gone?

I doubt it.

This is not true.

Although of course cotton was a relatively new product, underpants for women were not.

We know they’ve existed since at least Medieval times (link), there’s not a lot of evidence for them, but there wouldn’t be, it’s not really a subject you’d expect people to use precious vellum & ink to write about it.

Although I doubt Europeans, even the English, ever really stopped bathing with warm water, at least their hesitation seems to have only lasted a century or two, bathing returned from bathing-mad Germany.

The French also seemed to have helped improve bathing again:

To me the following bit suggests that it was indeed the upper classes who may have been particular about bathing & washing but that the common people weren’t that fussed, like this account from the 1790s shows;

Onwards to the 19th century;

It is interesting, although not surprising, that an extreme increase in population is often what resulted in hygiene declining.

We’ve seen this with Roman cities, early modern cities and here Victorian cities.

But we still see it today.

More people = more waste = overloading the system, infrastructure, etc.

Makes sense of course, but it’s good to keep in mind.

It’s not always people just giving up and not caring about hygiene but the situation just making it more difficult to keep it up.

Sounds familiar doesn’t it?

But this is about the Victorian era, not the middle ages.

This is the life the 19th century historians & authors knew when they created the image of the filthy middle ages that historians are busy trying to correct to this day.

I’ve often thought Victorians assumed Medieval cities were just as dirty as theirs, or even dirtier, so they could feel a little better about their own failings.

Luckily things soon changed, even the Victorians cared about hygiene as the text above shows.

But in the early 20th century things were still pretty bad for many, the following sounds in some ways worse than it was for many during the middle ages:

So far my sharing of the bits of this book I found most interesting.

Overall I enjoyed the book it was a fascinating read.

Unfortunately being unable to fact check a few claims, dubious translations and claims that no longer match what other historians have written on similar subjects, made me a bit doubtful of certain parts of the book.

Nevertheless it’s, by far, the best book I’ve read on the subject of the general history of hygiene.

One thought on “Book review: ‘Clean, a history of personal hygiene and purity’ by Virginia Smith (2008)”