I’ve just finished reading ‘Urban Bodies: Communal Health in Late Medieval English Towns and Cities’ by Carole Rawcliffe, Professor of Medieval History, University of East Anglia.

More about the book here.

If you still kind of belief medieval folks weren’t into bathing and didn’t mind living in towns were people just chucked waste into the streets, this is THE book for you. It is extremely detailed, deals with many subjects and is full of delicious sources & references.

The book is not just about hygiene & filth, also about care for the poor, medical knowledge, diets, disabilities, etc. I’m pretty sure it will change some of your ideas about the middle ages, even if you’ve been studying the subject for a very long time.

Yes, the book is about England but much of what you’ll read wasn’t much different in other parts of the world and when it comes to the idea of the dirty middle ages for some reason some people think that things were worse in England, so this book will come in handy regardless.

So I’m just going through the notes I made while reading the book, jumping from one topic to another, I’m sharing my thoughts here, not writing a detailed review. I can do what I want, I’m a grown-up! Sort of. And yes, I’m mostly focusing on the hygiene subject.

One thing I had not thought about much before reading this book is how some towns were practically obsessed with how visitors thought of their place. People invested time & money into making a good first impression on strangers!

Cleaning up the streets just so visitors would would think your town was a nice healthy place makes perfect sense but it still surprised me a bit when I read about it in this book, people really cared about this a lot.

Prof Rawcliffe btw also explains why the middle ages has had such a bad dirty reputation for such a long time. She also points her finger at the Victorians who witnessed a lot of filth & dirt in their cities but also experienced a lot of progress which made them contemptuous.

Victorian reformers & scientists did achieve some amazing things but it made them look down on those who had not reached that level yet but also on their ancestors. It made tem assume other civilisations, historical (& foreign?) were backwards.

The first chapter is titled ‘Less mud-slinging and more facts’. A title that made me smirk. Rawcliffe starts it with a scene from Monty Python & the Holy Grail. A great way to make me automatically like you. This chapter is all about the myths, bias, misconceptions, etc.

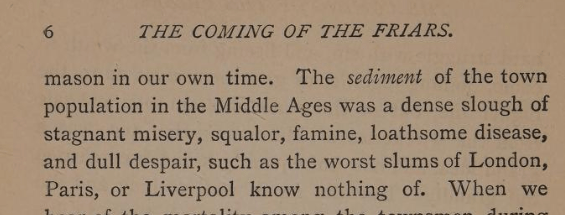

Rawcliffe gives some great examples of how the Victorians described the middle ages and how this became the accepted view for over a century. Like here in The coming of the Friars, and other historic essays (1890):

Sounds familiar doesn’t it? This perspective of the middle ages matched what Victorians saw in the slums of their own cities. Of course things couldn’t have been better in a time before theirs, right? We may laugh but be fair, many of us still feel a bit of…

Rawcliffe explains very well why you can easily believe the middle ages were either very dirty or clean, depending on how you look at the sources. For the Victorians there were TONS of medieval records that show the medieval cities WERE often filthy and disgusting but… the records were also full of solutions and steps taken to solve these problems and avoid them in the future. Some may interpret this as there being a lot of problems with filth, others may interpret this as there were the general amount of problems but they mostly got solved.

Another example: From ‘Public health in relation to air and water’, by Sir W.T. Gairdner, 1862:

The Victorian perspective became the generally accepted one that has been taught and repeated in books, schools, museums and later film & tv till this very day. Even when historians started to look properly at all the archives and more was learned, the old view remained popular.

Historians were trying to get rid off this simplistic one sided view as long back as the Victorian era but it seems that they were not given a lot of attention. Somehow the image of dirty medieval cities was appealing. Victorian cities were filthy, they had slums & poverty.

One of the earlier historians who fought this perspective was G.T. Salusbury who published ‘Street life in Medieval England‘ in 1939, he actually went to check the primary sources and wrote about the solutions as well as the problems.

We point at the Victorians for not doing their homework properly but books & documentaries that just repeat these ideas without actually checking the original sources and turning the page to see what was written after the records mention a problem are still being published today.

Medieval records write a lot about issues with waste, water & filth, but they also write a lot about what was then done about it. This was sometimes ignored by later historians. Rawcliffe also mentions what I often say; Roman cities were filthy but few people talk about that.

Think to yourself, how come we think medieval cities were dirty but somehow don’t automatically have that view of Roman cities? They had waste problems, disease outbreaks, slums, etc. Often worse than medieval cities had. For some reason we like Romans to appear better.

Rawcliffe mentions many of the problems medieval cities had but then also, as one should, explains what was done about them. Medieval people didn’t like filth, yes I know, shocking news, they even had functioning noses, amazing discovery, I’m sure.

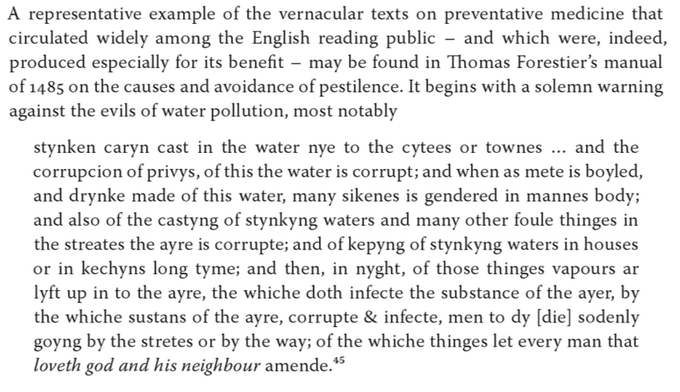

Remember, medieval people believed in the Miasma theory (just like the Ancient Greeks, Romans, Ancient Chinese, Indians etc) so to them bad smells were not just unpleasant, they were dangerous, they could damage your health so if there was a stinky mess it had to be taken care of.

Rawcliffe gives many examples. People make a mess, neighbours explain, rulers get involved, ordinances written, fines handed out, industries moved to outside the town walls, problems solved, for a while anyway.

Which is pretty much how things still work today in much of the world. In some cases, like during the Black Death pandemic the Crown got involved, the king started ordering cities to clean up streets after lots of people dying had put an end to this work being done.

Of course hygiene and everything else suffered immensely during the pandemic, but because people feared smells might be one of the reasons people got sick, Edward III forced the mayors of some towns to get back to cleaning streets, even as it seemed to be the end of the world.

In Italy they went further, they forbade people moving about (a sort of lockdown), placed embargoes on transport of cloth, curbed industrial pollution, cleaned streets & sewers, etc. Society collapsed in many aspects, but people still tried to keep things clean.

English guilds were also involved in keeping the places of their industry clean but also watercourses unpolluted and working well. Water was flowing from outside towns to workshops but also private houses and lots of rules were made to keep all this working properly.

There were sometimes rules about being clean and getting towns and cities cleaner that came directly from the top, from the king. But often it was also a communal thing, sometimes the people wanted, which again makes sense, people had to live in these towns!

People were campaigning, complaining, protesting and gathering funds to clean their cities, get clean water, move polluting industries away from their neighbourhoods, etc. Huge amounts of money were invested and lots of work done. Yet some think nobody cared…

When in Oxford people complained about the many pigs people kept, the king himself ordered something to be done and when this didn’t happen fast enough the mayor & bailiffs were given a serious reprimand.

Then people of Oxford complained about the state of the pavements and this time the king threatened the mayor & bailiffs with serious punishment. People cared about filth, they complained, their complaints sometimes made it to court and you didn’t want to annoy the king…

While Victorian historians wrote that medieval peasants accepted living in filth and were fine with it, Victorians living in a poor part of London explained how he felt about living in filth in The Examiner of 1849:

One example of medieval people caring about hygiene is the famous 1393 guidebook ‘Le Ménagier de Paris‘, it explains how the wife is expected to fight vermin but also make sure there’s always hot water for washing, there had to be freshly laundered linen, etc.

Medieval people had basins, ewers, tubs, soap, sponges, towels, etc. We know this from testaments. And although the wealthy had of course more and nicer stuff, it wasn’t just them who had hygiene related objects at home.

Medieval people embraced bathing & washing, the enthusiastically took part in the rituals and pleasures of everything involved with being clean. But not just their body, also their (under) clothes. People knew lice liked dirty clothes, people hated lice… so…

Learned men said that dirty clothes, insanitary habits & skin disease were all related. People wanted their cities to be clean and diseases & vermin avoided. So if you let your servants or apprentices live in filth, you could get send to jail!

When records say people should avoid baths, they sometimes meant bath HOUSES, not bathing. During a pandemic it is a good idea to avoid places where people get together and where travellers often first go when they arrive.

Another interesting perspective is that some of the complaints in the records are always about the same people or industry. One bad egg in a relatively decent neighbourhood could cause pollution that upset everyone and sometimes they just didn’t want to learn.

This of course still happens today. But the idea that one person or one workshop caused all the pollution that filled the records of one town does give us a different perspective. It’s not like the entire town was being dirty, just filthy old Dave, again.

But also industries such as butchery, tanning, markets, etc. regularly caused pollution and filth. And again people got upset, complained and solutions were implemented. Again and again: yes there was filth, no people weren’t fine with it, yes the problem got solved.

The book is full of such examples. Pavements were installed, street cleaners hired, fines handed out. Just like today. Except back then people got scared whenever there was a disease outbreak, thought perhaps filth had to do with it and rules became stricter.

Rawcliffe also writes a fair bit about pavements and street cleaning. She explains that paved streets were more common than people seem to think and that this started quite early.

Dung carts were used to collect waste, certain industries were ordered to only use one specific place for dumping waste. In York and London every ward had their own refuse cart, again just like today except we use garbage trucks and have more waste.

Rawcliffe also did a lot of research into cesspits, they were all over the place, some very well made, others improvised. But all had to abide with strict laws and building regulations. They became better & more regulated after the Black Death, again because of the fear of stink.

People were terrified of stench and a lot of effort was put into preventing seepage, as strange as it may sound people didn’t like feces & urine to become mixed with the ground water they drank & used for washing… In some places the content was regularly collected, at night.

Those who could afford it had indoor privies with chutes leading into covered cesspits behind the house. Like a private sewer. But even those who couldn’t afford a fancy cesspit, tried to avoid pollution by for instance putting a barrel in a pit, like here in Denmark:

People cared about their privies and kept them clean, they sometimes even put it int heir will, demanding that their kids maintained them properly. If your cesspit annoyed your neighbours or polluted the water supply you could end up in court.

People also complained about noise and smoke, not just smells & filth. An armourers workshop drove its neighbours mad with the continues hammering. The folks next door were also afraid this reduced the value of their property. Which again sounds like something that happens today.

People also complained about neighbours who partied all night… I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: our ancestors are more like us than many of us realise or want to accept. Rawcliffe also writes about cisterns & conduits which supplied people with clean water.

These were a lot more common than I thought but many people don’t even know they existed. It’s the medieval equivalent of the Roman aqueducts everybody knows about… It was often friars who set up systems for clean water but they then shared it with the villagers nearby.

Which makes sense as their water pipes and canals often went through land of local people but they also did it for goodwill and philanthropic ideals. In 1428 the town of Lynn invested a fortune in a kettle mill, a wheel with buckets that then poured water in a leaden gutter.

Just one of the many examples showing us that medieval people connected filth and bad hygiene with the very deadly diseases they were terrified of, again: they didn’t like filth, bad smells & lousy hygiene!!!

Medieval towns had drains, often covered but I guess not covered enough to be compared to sewers… 😉 Medieval records show that polluting or endangering the water supply was severely punished. If you dumped waste in or near the water supply you were in serious trouble.

Does that fit the old myth of medieval people drinking beer in stead of water because the water was always polluted? There was a widespread awareness of contaminated water could cause illness or even death. It’s a lesson you learn very quickly…

Most people throughout history seemed to have known yet somehow some still think the medieval folks forgot all about it for a couple of centuries… Even if you didn’t trust local water from the well or waterhole in your yard, conduits brought spring water from outside town.

But even though there were gutters in streets, covered and uncovered, you still couldn’t just pour anything you wanted into it. It was only meant for used water, liquid waste easily flushed away. Pouring anything else into it could again get you in trouble.

Rawcliffe accuses the Dutch community in Ipswich for getting locals hooked on beer in stead of ale. Which made me proud 😉

I’m sure you’ve heard the medieval Thames was filthy and very polluted yet in 1364 an apprentice was arrested for throwing rubbish into it.

The book also mentions how the sick and poor were cared for, the bakery industry, the brewing business, prostitution, health care, the homeless and many more subjects. Pretty much every chapter taught me something new and changed my perspective a bit.

Rawcliffe concludes with the claim that the idea of medieval England’s public health were terrible is outdated and we need to move past the Victorian ideas. England did not trail far behind the sanitary regulations of the continent.

In short the book proves and supports what many historians and I have been trying to tell people, but she does it with a LOT more sources, references and study than I can ever offer you. So, as the super long length of this thread shows; I love this book and so does Beike:

If you still think medieval cities/towns/people were filthy and didn’t care, read the book. If you know someone who does, send them the book.

PS: here is a lecture by professor Rawcliffe which starts with Monty Python’s sketch!

Are there more information regarding about this topic for us to research for? Thank you, Regard Telkom University

LikeLike