This book is a classic, very well known, but it’s almost as old as I am.

I always warn people about old history books, we learn new things about the past almost every day, not just because of archaeological finds, new technology such as DNA but also because there are so many records that simply haven’t been researched yet.

So it really doesn’t take long before a history book can be considered outdated.

For instance, books that seriously look at hygiene in medieval Europe based on actual records in stead of just repeating what earlier historians thought, are shockingly recent, something that wasn’t much of a thing till this side of AD 2000.

Keeping that in mind, there’s a reason I still wanted to review this book.

Not only is it a great book, but it was also its time ahead in quite a few ways.

Making it both an old book but not that outdated.

It’s also about daily life for common people, my favourite subject.

What makes this book so unique for its time?

Hanawalt used historical records for her research, not battle reports, political writings, etc. but the day to day paperwork of the courts.

Today that is quite common, as the topic of what life was like for peasants has become more popular, more and more historians vanish into the archives to go through countless pages of mundane paperwork.

But in the 1980s this was not that common a way way of looking at things.

Besides finding out a lot about what life really was like, we also get the wonderful experience of learning the names and stories of people who else would have vanished into the mists of time.

For instance here is one of the many examples you’ll find in this book.

If it had not been for his terrible misfortune, we likely never even would have known John existed:

Anyway, I’m just going through the book and share some of the bits I find most interesting.

One thing to also keep in mind is that the book is, as the title mentioned, about Medieval England.

So although much of what we’ll read would also match what things were like in other Medieval cities, some would also have been very different there.

The more things change, the more they stay the same…:

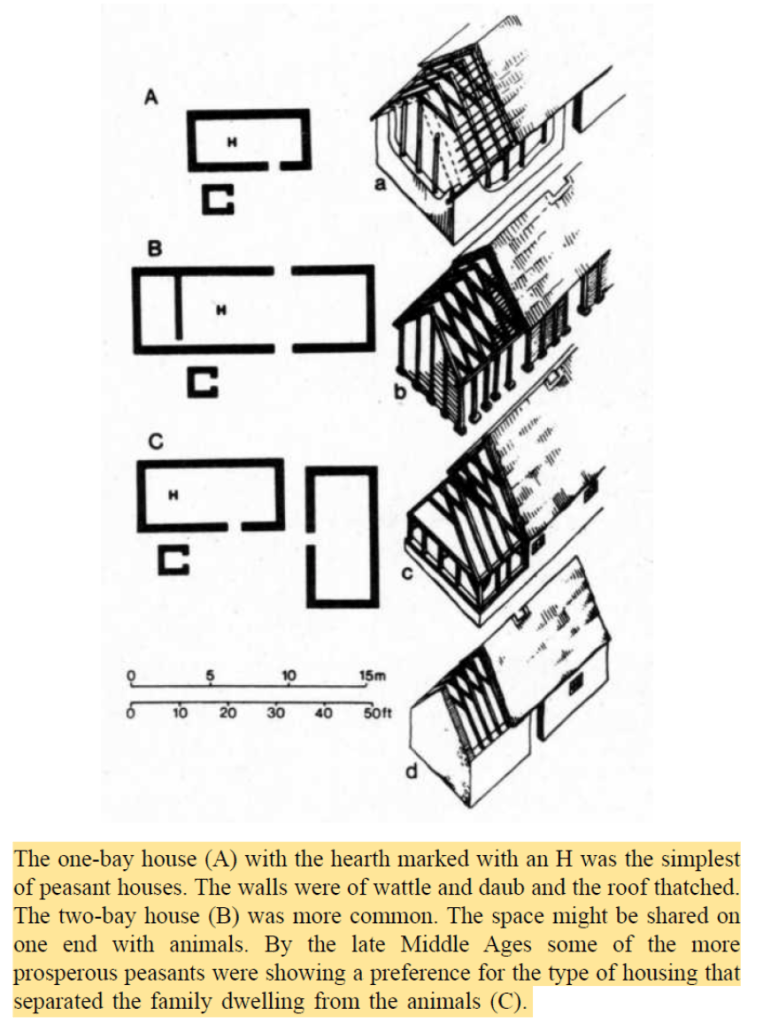

A common misconception about the middle ages is that people shared their living spaces with cattle.

You can read more about why that is mostly a myth here:

https://fakehistoryhunter.net/2025/11/15/did-medieval-people-share-their-homes-with-cattle/

But this nice illustration shows what peasant houses would have been like and explains that the cattle often had their own space:

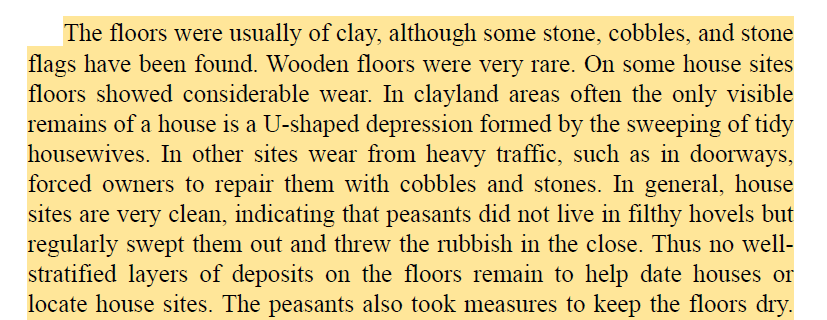

A good description of what these houses would be like from the inside and wonderful confirmation that we have no evidence of these places being filthy, but we have some that suggests the opposite:

What the straw covered floors mentioned in the next quote looked like is still hotly debated by historians, well, especially by me.

I believe that they didn’t just throw random loose straw (rushes) all over the place but usually wove them together, roughly or neatly, or packed bundles close together.

But I’ll write about that in another article some day.

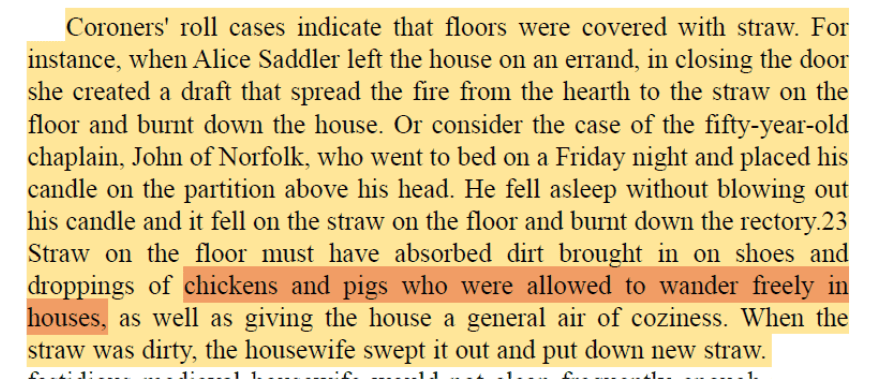

Either way, straw does catch fire easily.

I do have to disagree with the claim that chickens & pigs were allowed to wander freely in houses.

We know they sometimes did, but I’m yet to find convincing evidence that suggests that they were allowed to do so.

I mean, how do we know for sure that these cases of where animals caused havoc indoors they had let themselves in?

We know from the records that pigs were known to cause severe damage and literally killed children, which makes it hard to believe they would have just been allowed to walk in and out of the house.

More about medieval pigs here:

https://fakehistoryhunter.net/2024/08/05/book-review-the-medieval-pig-by-dolly-jorgensen/

For instance, in this case nobody assumes the bear was allowed to wander freely:

A nice mention of people having their own well/pit in the yard or place behind their home, people often assume that hygiene suffered because it was such a hassle to go get water from far away for everything, but wells and fountains were really quite common and relatively close by:

More evidence of people having access to clean water that they used for more than just drinking:

I love it when the evidence shows that medieval people weren’t the mucky filthy weirdos that we’re still often told they were.

Mind you, the medieval family had very little waste, food & other biological waste ended up on a heap in the yard, everything else was recycled, this included bones, broken pottery, etc:

The following seems to clash with what the book just mentioned and what we know from other, more recent books but these were complaints, so we’re reading about cases where someone dumped their waste in the wrong spot and were ordered to move it.

Also free bonus horrific murder story that to me suggests that these dung heaps outside doors may not have been what they sound like.

I mean would you drag a body to a heap outside your front door on a public street?

Or was this particular dungheap perhaps by the backdoor?

I love what these records of thefts tell us about the past, how things that to us modern people don’t sound like they’d be very valuable, were so for medieval people.

Of course everything then was handmade and a lot more expensive than today:

But the records also give us an idea of how little poor people owned, also that lord was a bastard:

I also love how these records can be combined with other sources to give us a better idea of how homes were decorated, I especially like the details about how there was always a fire burning and liquids warming there, people sometimes think medieval people didn’t bathe/wash much because warming water would be such a chore.

But it seems like they almost always had warm water ready:

Although medieval people likely didn’t smell much (they washed, used soap & were terrified of bad smells), the book reminds us that the main smell you’d notice if you would go back with your time machine, was the smell of smoke:

Casually debunking the idea of the medieval diet being bland and not nutritious:

The following makes sense, after all the medieval diet contained no/little refined sugar/starch/carbohydrates/tobacco/caffeine:

Does this fit your idea of what kind of food would be given to the poor:

Hahaha, I love this story and totally deny having been in a similar situation:

These records show us that peasants also cared about having clean hands and tables while eating, that they kept their hands clean:

Excellent piece on medieval hygiene but the red part needs a note.

These days we believe that most bathhouses were not used for prostitution, unfortunately medieval records sometimes used the same word for bathhouses & brothels: namely stews.

But we know that in many prostitutes were not welcome and that they were used by families, that you’d meet your neighbours there, that they weren’t really suitable for naughty games.

Read more about that in my review of Urban Bodies: Communal Health in Late Medieval English Towns and Cities’ by Carole Rawcliffe (2013), ‘Het middeleeuwse openbare badhuis’ by Fabiola van Dam (2020), and ‘Community, Urban Health and Environment in the Late Medieval Low Countries’ by Janna Coomans (2021):

More fascinating details regarding hygiene, people were literally risking their lives bathing, washed their hands, from the recent books I just mentioned we get the idea that a weekly visit to the bathhouse was pretty common:

A bit on how old people were when they got married, a lot of folks today still believe that child marriage was common in Medieval Europe and that people at least married young, but in much of Europe this was not the case.

I’ll write more about that in a different article.

But this here shows that in an extreme situation, the age of marriage still didn’t go lower than late teens:

Let’s raise a glass to this brave dad:

This story got to me, so I had to check Hanawalt’s other book (Crime and Conflict in English Communities, 1300-1348) for more details:

Praise be to Richard and I hope Walter is spending eternity in hell.

Anyway, does what you’ve just read fit what you’ve been told about how women were treated, valued and protected in Medieval Europe?

But what about the canon law that allowed marriage at a young age?

I like how Hanawalt here explains that things were different in Italy by using the famous story of Romeo and Juliet:

So how many babies did people actually have?

We know that people had access to birth control, but how common this was is difficult to say:

The image we have of large families is more from much later:

We often hear that there were strict laws about “hunting & gathering” because the land belonged to the lords, but learning that they weren’t always hanged on the spot but fined and that the fines were very low gives that a whole different perspective, not that some were not punished severely, but still:

And the book keeps giving us these amazing but sometimes horrible little dramas, goodness me, what a horrible accident:

One of the illustrations from the book, it comes from my favourite medieval book, the Lutrell psalter, Hanawalt used it to explain that both men and women worked to bring in the harvest:

In some parts of Europe daughters & sons got equal inheritance, like in the low countries.

You can read more about that here; Urban Bodies: Communal Health in Late Medieval English Towns and Cities’ by Carole Rawcliffe (2013).

But this was very uncommon, in England she didn’t always get the same, but still something;

Another example of how looking at records like these give another insight into the reality of daily life:

This is fascinating, Hanawalt describes how our perspective can sometimes be influenced by what we know of an other era;

I’ve portrayed the life of a medieval woman in an open air museum in the Netherlands where I literally had my own house to look after.

And I must admit that every time I waste a day cleaning the damn white tiled floor in my house, I think back to when I just had to brush a dirt floor in the middle ages.

It was so much less work.

I’ve already shared my doubts about animals being allowed to walk in and out, but I love that we have literal evidence of floors being swept:

A bit on how much people earned… look at that, men & women being paid for the same work, what a novel idea, we could learn from that…

More about how women made a living, yes they didn’t just stayed home to look after the kids, women not working is quite a recent thing in history.

Also I love getting to know Mabel, the tree thief:

Medieval women were not the powerless domestic slaves they’re often portrayed as, they had more rights and opportunities than women have in some countries today:

What? No clubbing & drinking?

Then why bother?!!

More evidence of women having rights and having those protected by the court:

These records are so interesting but also so terrible and heartbreaking:

But these horrible accidents give us an insight into the kind of jobs sons & daughters had to do from real life examples in stead of adults writing about how you should raise your kids:

Poor little John, what a horrific scene, a death you’d expect in a Charles Dickens novel, but real:

Girls worked hard, I bet medieval girls had better abs and biceps than quite a few modern day gym-bros….

Yes, until not that long ago historians thought that medieval kids didn’t really have a childhood and were just treated like small adults.

That perspective has changed, in part due to records like these:

Dear gods, is there no end to these terrible stories?

Poor poor William, his poor mum:

More details about the lives of women:

It was indeed quite common for children/teenagers worked away from home, but not just work, these were also apprenticeships, this too explains why in Europe people didn’t get married later:

Average life expectancy was low in Medieval Europe, average being the key word.

But this is of course a skewed perspective because the number was low due to high child mortality.

However, it was not just childhood diseases that killed so many children:

As someone who owns chickens, I still doubt that these fires were caught by chickens who just wandered in and out of houses.

I think they walked in when someone wasn’t paying attention and left a door open.

I just find it hard to imagine that people who cared about sweeping their floors wouldn’t mind chickens coming in and making a mess.

Not to mention that they like scratching the ground, turning your carefully compacted, stamped floor into rubble:

Another lovely illustration from the book showing an intimate but familiar daily scene, mum cooking with a baby on her lap and another kid helping out:

Poor poor family:

Before you ask, yes medieval people were shocked by these stories too and didn’t approve:

It’s still wild to me that for quite some time many historians believed that Medieval parents didn’t care as much about their children as we do, I’m glad that this perspective has practically died out.

Medieval parents loved their children:

Another little legal drama telling us so much about the rights women had and how young people were not considered adults till relatively late:

Arranged marriage were not as common as many people still believe and in reality how people lived together and how their relationships worked were a lot more free, in some of the other books I mentioned earlier we have examples of couples living together and even having babies without being married and this being generally tolerated:

A bit on widowhood.

It is interesting to see how in many ways becoming a widow came with quite a few opportunities and even improvements in the lives of women.

They inherited but also could take over their husbands job, sometimes literally:

Remember how often you’ve been told that medieval people didn’t live long?

This way of looking after the elderly is still a thing.

My dad used to tell me about a rich man who promised to look after a little old lady if he could have her big expensive house after she died, which was not a fair deal, the house was worth much more than what he was giving in return.

But the little old lady decided to live another couple of decades and outlived the man, so she had all her bills paid and still kept her house.

Mind you, in a time before governments did the decent and civilised thing and made sure all people were looked after in their old age, this is a pretty decent alternative, although not available to all of course:

Here the details of one such contract tells us a bit about what the medieval person considered to be important in life and what these things would cost them:

But these deals were not just made for individuals themselves, sometimes they were made for those they left behind, like lovely John here who made sure his widow would be taken care of:

Poor Alice, her life must have been so difficult.

Medieval people experienced a level of poverty we can’t even imagine.

But I can’t help thinking that if she had not drowned, there may not even have been a record of her existence, we would have never heard of her;

Here my review ends.

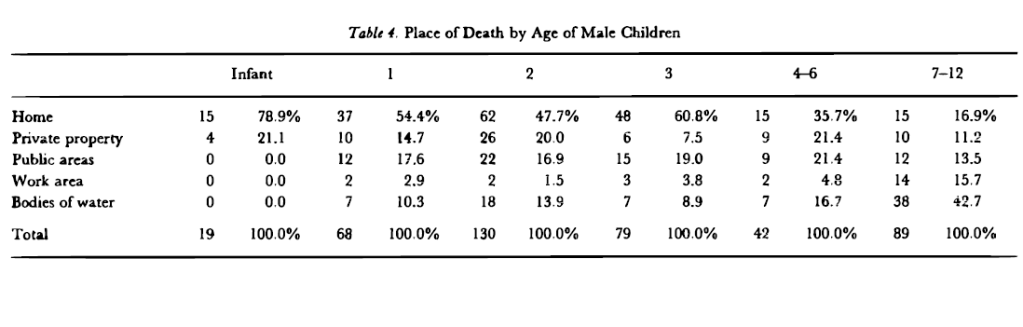

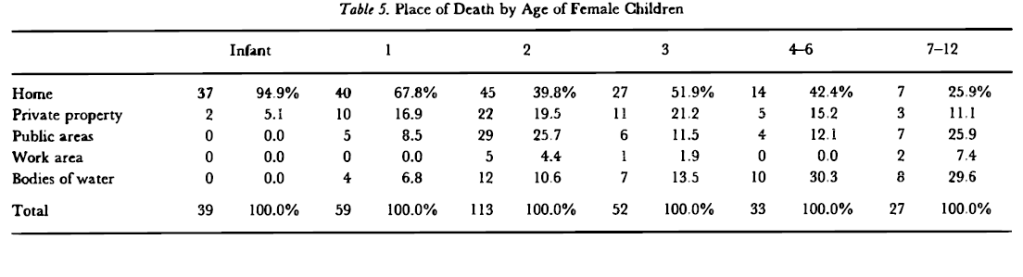

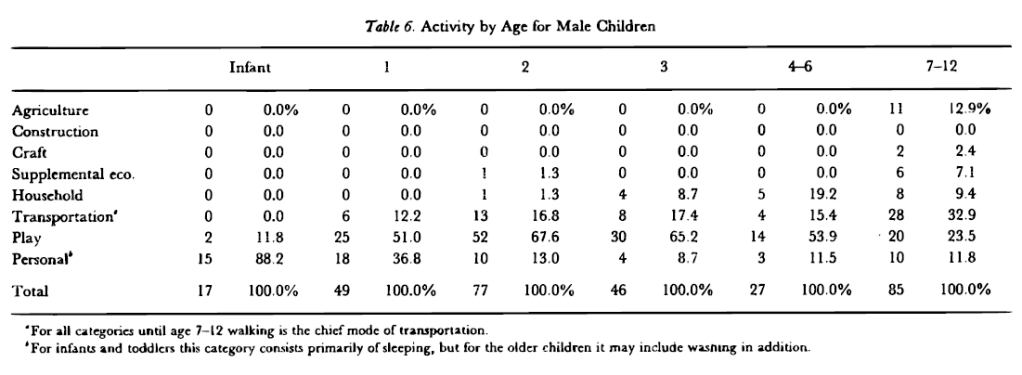

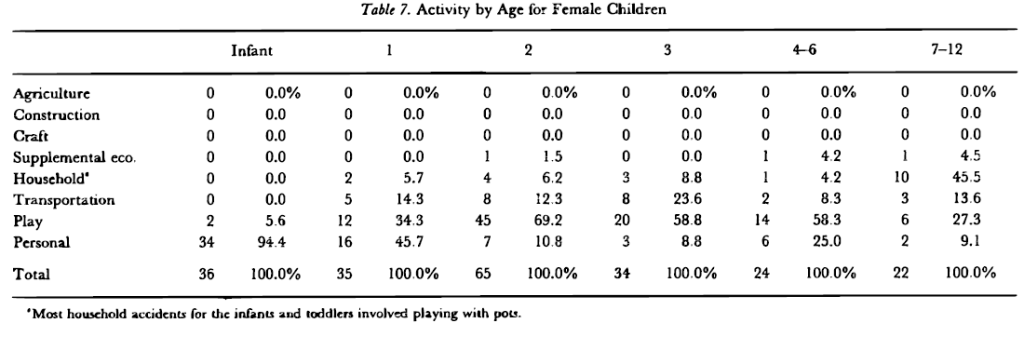

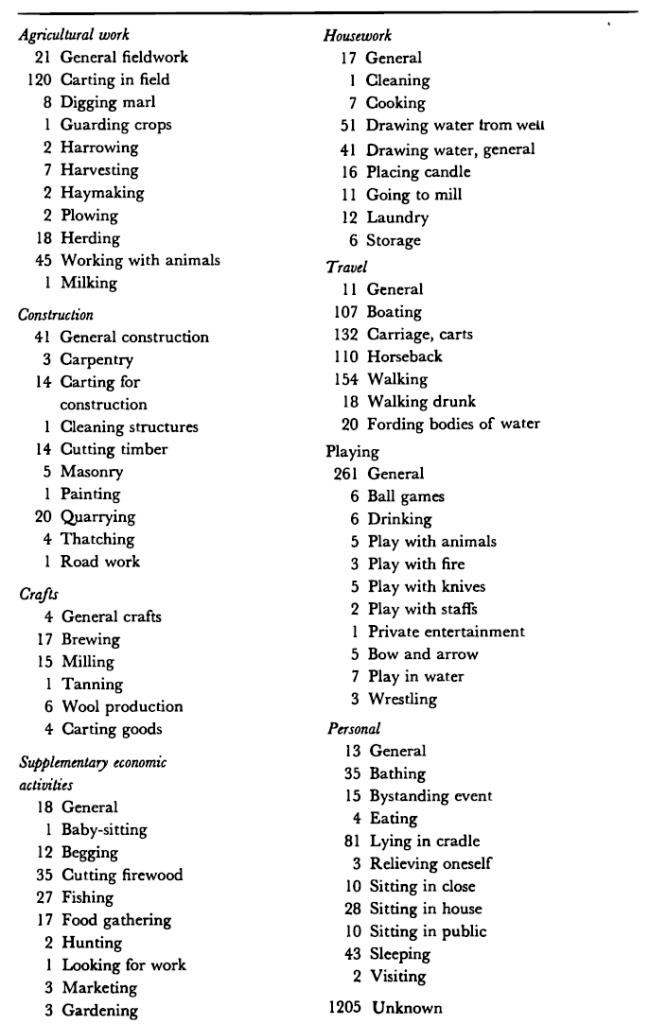

In the back of the book we find a few more interesting tables I want to share as well, these relate to the coroner’s rolls:

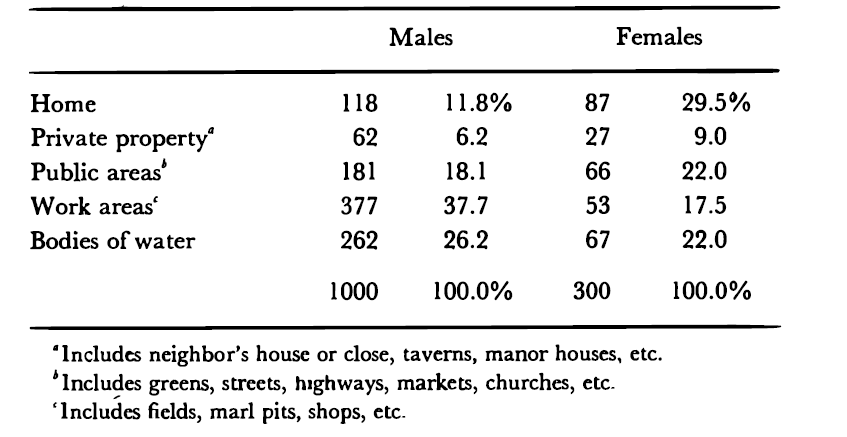

Table 1. Adult Males and Females: Place of Accident:

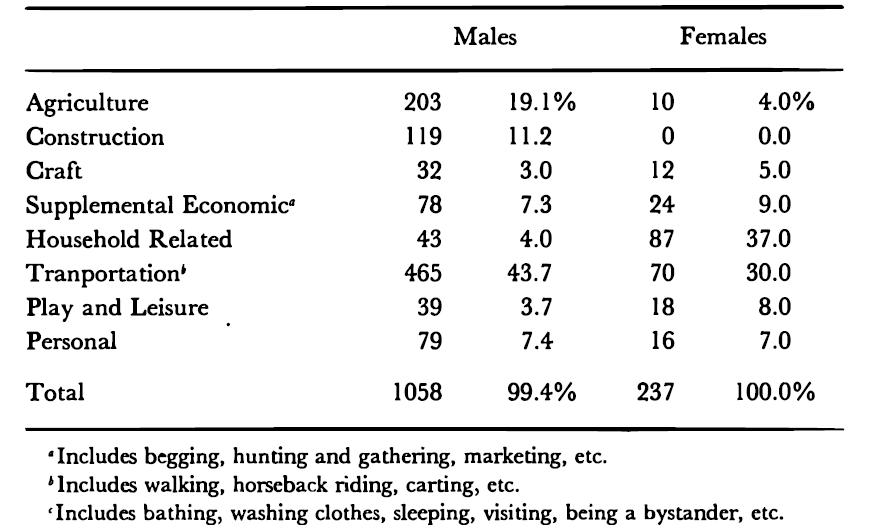

Table 2. Adult Males and Females: Activity

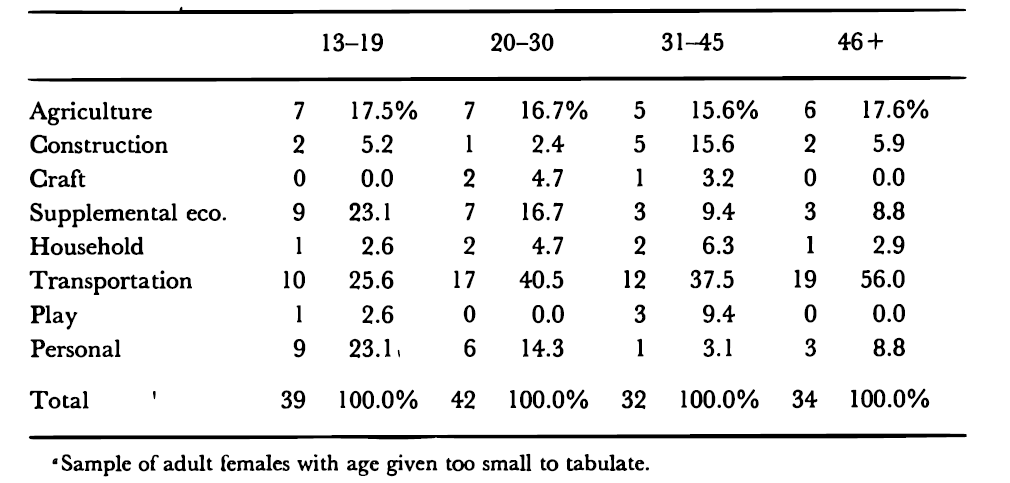

Table 3. Adult Males: Activity by Age

Table 8. Activities at Time of Victim’s Death: Aggregate Numbers

Fascinating stuff!

So, conclusion.

This is a great book, a masterpiece.

Even though it’s an old book, there’s very little in there that I consider to be outdated, Hanawalt did an amazing amount of research and went though an incredible amount of sources.

The result is a book that gives us a whole new and unique perspective on what life was really like back then, purely based on what medieval people themselves left for us to read.

Which is why this book in some ways was ahead of its time.

I absolutely recommend it.